The return of The Family Man was expected to revive a franchise that once blended realism, humour and national-security storytelling with relatable domestic tension. Season 3, however, lands differently. Beneath its pace, performances and scenic production lies a troubling pattern that many viewers have flagged but very few mainstream critics have spoken about directly.

A pattern where Hindu rituals are trivialised, Indian institutions are compromised almost casually, and the primary enemies of the nation are now Indians themselves, while foreign adversaries stand blurred in the background.

This is not accidental. The structure of the season, scene by scene, reinforces an ideological undercurrent that leaves many viewers unsettled.

Scene 1: The Griha-Pravesh That Wasn’t a Ritual, but a Punchline

Season 3 opens with intensity in Nagaland, followed by an abrupt cut to the Tiwari family’s griha-pravesh as they shift into a new flat. This is Episode 1, very early in the domestic segment, immediately after the Nagaland blast sequence.

Multiple viewer reactions circulating on public forums note that the pooja is treated as a comedic prop. The pandit, the holy set-up and the ritual process are punctured with derogatory slang including words like “gendpat” and “veerya,” delivered casually while characters sit around the havan.

The placement is deliberate: the season’s tone-setter for the “family” component is built not on reverence or normalcy but on mockery and reduction. Children watching this scene are presented with a version of griha-pravesh that frames the ritual as pointless, funny and archaic.

This is not a creative liberty issue. It is a framing issue. When a sacred domestic milestone is reduced to a skit, it signals a creative choice about which parts of Indian culture deserve respect and which can be treated as throwaway humour.

Scene 2: Alcohol Ritualised as Spiritual Offering

One of the more culturally sensitive sequences involves Rukma and Meera. In a quiet moment, Rukma offers Meera apong a rice-based alcohol traditional to certain communities of the North East. Before drinking, he flicks a portion onto the ground as an “offering to spirits.”

This appears in Episode 2 or 3, during a private exchange between the two characters.

What the viewer sees is a ritual-like act attached to alcohol consumption. NDTV’s coverage of the drink explains that the sprinkling is part of local custom. But within the universe of the show, the creative treatment links the invocation of spirits to alcohol in a way that lends itself to caricature when viewed through a mainstream national lens.

In a season already leaning heavily on distorting Hindu symbology, the proximity of an “offering” to alcohol adds another layer to the pattern: sacred, mystical or ritualistic elements appear only in contexts that trivialise them.

Scene 3: The Villain Named Dwarkanath

Perhaps the strongest symbolic statement is the naming of the main antagonist: Dwarkanath.

This is not a random choice. “Dwarka” is inseparable from the cultural imagination surrounding Lord Krishna.

“द्वारकानाथ” एक संस्कृत/भारतीय धार्मिक नाम है, जिसका अर्थ है:

द्वारका + नाथ = द्वारका का स्वामी

यानी भगवान कृष्ण।

The season could have used any corporate name for its antagonist. Instead, it leans on a name with deep religious resonance and then attaches it to:

- Manipulation of a defence deal

- Violence in the North East

- A covert nexus with international arms lobbies

- The orchestration of killings, chaos and political disruption

The narrative, backed by multiple reviews, shows that Dwarkanath is central to “The Collective” a shadow entity working with foreign defence companies. His motivations are not patriotic, not ideological; they are commercial.

The symbolic inversion becomes clear.

A name culturally tied to divinity is used to front deceit, greed and national sabotage.

Scene 4: Corruption Inside the Indian State Treated as Routine

As the plot advances, two major twists reveal the extent of insider betrayal:

- Sambit, a high-ranking government advisor, is shown in regular contact with Dwarkanath, leaking information and pushing the defence deal forward.

- Yatish Chawla, who replaces Srikant, leaks intelligence to Meera and Rukma in exchange for payment.

These arcs unfold in Episodes 5 and 6.

The treatment is casual and un shockingly normalised. The show does not present their fall as tragic or morally heavy simply transactional. The narrative seems almost comfortable with the idea that people closest to national leadership can sell the country for money.

What the viewer registers is a consistent message: when the nation falters, it is not because of enemies outside, but because of rot within. That may be an interesting political argument, but in this season, it is not handled with nuance; it is amplified without counterbalance.

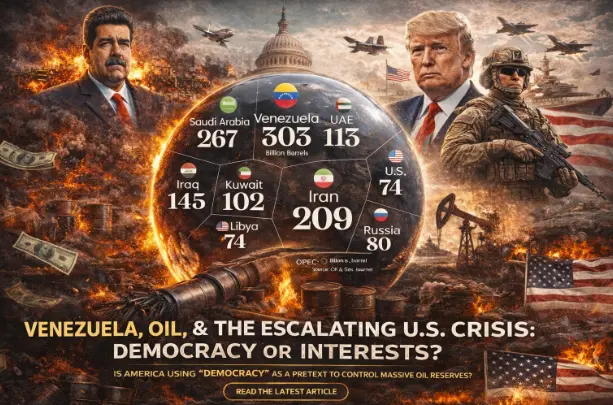

Scene 5: Foreign Enemies Softened, Indian Rebels Elevated

Earlier seasons painted external threats vividly ISIS modules, Pakistani networks, foreign handlers. Season 3 dilutes this.

This time:

- The ISI appears, but with weak presence and little narrative weight.

- China’s expansionist strategy is referenced but not positioned as the primary driving force.

- Western arms dealers and Indian insiders dominate the threat landscape.

- Insurgent and naxal-coded groups in the North East become the central instruments of chaos.

Foreign adversaries seem almost bored or incompetent, while Indian factions carry the plot’s danger.

The outcome is a reorientation:

the nation’s danger is no longer foreign hostility but Indian culture, Indian citizens, Indian leaders and Indian belief systems.

This is a very deliberate ideological framing.

The Pattern Is the Point

Individually, any one of these choices could be defended as narrative freedom. Together, they form a pattern that is difficult to ignore:

- Mock a Hindu household ritual at the very beginning.

- Show a sacred-sounding “offering” tied to alcohol in a cultural moment.

- Name the central villain after a symbolically divine figure.

- Portray top Indian officials as willing agents of foreign arms lobbies.

- Minimise external enemies, maximising internal decay.

This is not a critique of India.

It is a caricature of India.

And it constructs an ideological world where Indian culture is backward, Indian institutions are broken and Indian spirituality is comic material.

A Show That Has Shifted its Moral Compass

The earlier seasons of The Family Man balanced cynicism with affection. India’s flaws existed, but its institutions had soul and its culture had dignity.

Season 3 abandons that balance.

It leans on spectacle, clever staging and political ambition, but the moral centre the “family” and the “man” feels eroded.

This is why the backlash feels sharper.

The disappointment is not about pacing or cliffhangers.

It is about the cultural undercurrent that the show has now normalised.

Viewer Reactions: A Season That Felt Surprisingly Hollow

After watching the entire season, a lot of viewers felt disappointed. A number of emotional sequences were rushed or left unexplored, and the writing felt thinner than anticipated. Important connections that had previously given the narrative depth were ignored, and characters who ought to have grown as a result of earlier incidents appeared strangely reset. The remaining part of the season felt like a diluted version of what the series once promised, with only a few subplots managing to maintain viewer interest.